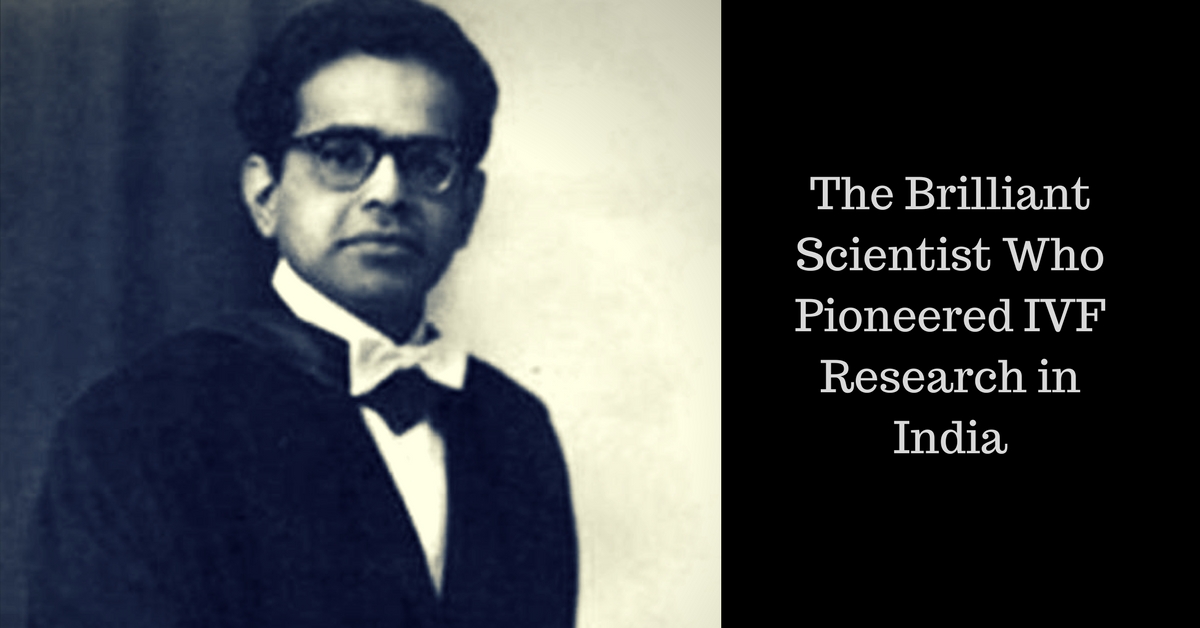

Denied Recognition, This Path-Breaking Doctor Created India’s First Test Tube Baby

A path-breaking doctor few Indians know about, Subhash Mukherjee created India's first and the world's second test tube baby using in-vitro fertilisation.

On August 6, 1986, India officially entered the brave new world of assisted conception with the widely publicized birth of its first ‘scientifically documented’ IVF baby, Harsha Shah.

Eleven years later, TC Anand Kumar — the pioneering doctor who collaborated with gynaecologist Indira Hinduja to create India’s first test-tube baby — realized that the title he bore belonged to someone else. Kumar had been browsing through some documents he had received at the recently-held Science Congress when he came across the handwritten notes of Dr Subhash Mukherjee.

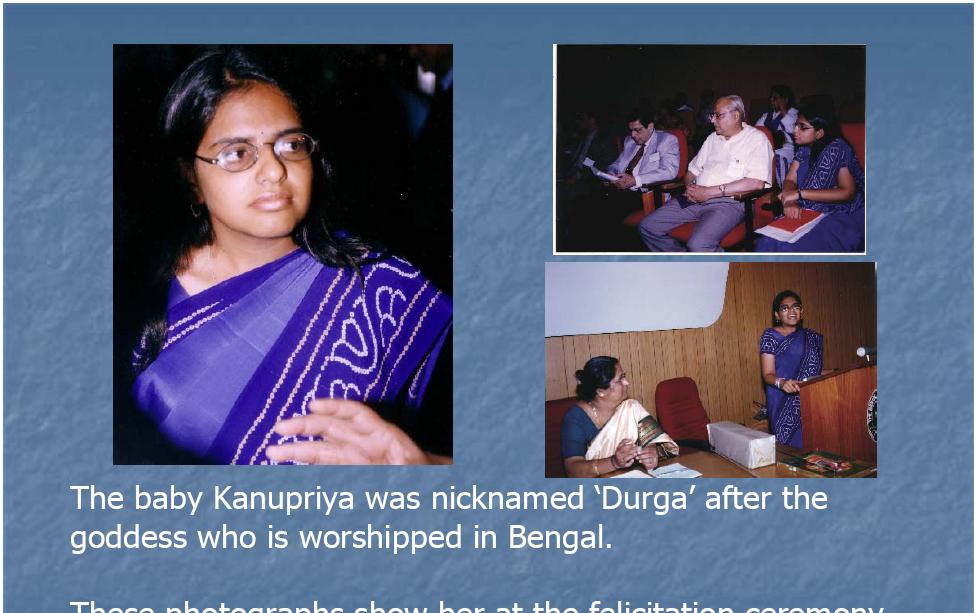

Meticulous scrutiny and cross-verification made Anand Kumar conclude that the Bengali doctor had preceded him by eight years — India’s first test-tube baby, Kanupriya Agarwal alias Durga, had already been born on October 3, 1978, in Kolkata.

Durga was also the world’s second test-tube baby, born just 67 days after the headline-grabbing birth of Marie Louise Brown in England!

Shocked that the incredible feat had received almost no acknowledgement from India’s scientific community, Anand Kumar took the courageous decision of researching Subhash’s findings and scientifically presenting it to the world, giving the forgotten doctor his due place in medical history.

In his speech at 3rd National Congress on Assisted Reproductive Technology held in Calcutta on February 8, 1997, he made an appeal that Subhash Mukherjee should be credited posthumously for creating India’s first test-tube baby. Two months later, he followed up his appeal with the publication of an article in the journal Current Science, entitled ‘Architect of India’s first test tube baby: Dr Subhash Mukherjee‘.

Thanks to this article and Anand Kumar’s tireless efforts, the Indian scientific world belatedly woke up to monumental nature of the medical achievement.

However, it was only in 2002 that the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) formally recognised the efforts of the forgotten genius. Nonetheless, this pioneering doctor remains little-known among Indians, his path-breaking work unsung and his contribution to modern science overlooked. Its time this changed.

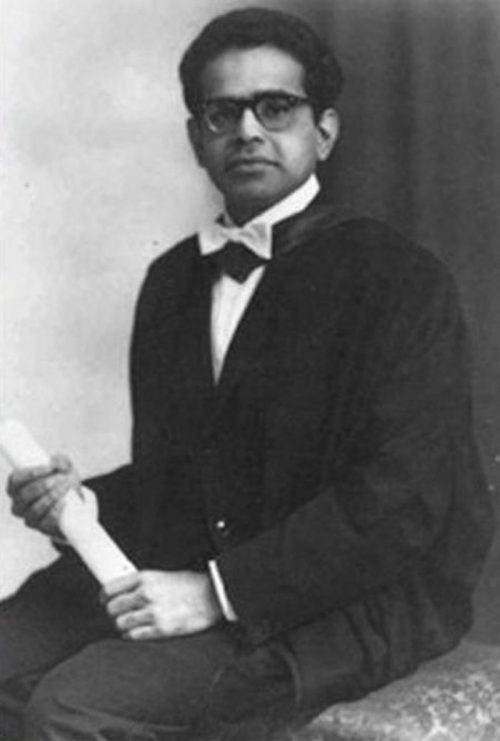

Born on January 16, 1931, in Hazaribagh district of present-day Jharkhand, Subhash was the son of a doctor and studied at the National Medical College in Kolkata after completing his schooling. Fascinated by innovations in gynaecological surgery from his early days as a medical student, he completed his PhD in reproductive physiology from the University of Calcutta before going to Edinburgh University in the UK for a PhD in reproductive endocrinology.

On his return to India in 1967, the dedicated doctor started researching ovulation and spermatogenesis. Soon after, he teamed up with Sunit Mukherji, a cryobiologist, and Saroj Kanti Bhattacharya, a gynaecologist, to work on a method of in-vitro fertilization for a patient (Bela Agarwal) with damaged fallopian tubes.

On October 3, 1978, Subhash and his team announced the birth of the world’s second test tube baby in Calcutta, a baby girl who was nicknamed Durga after the Hindu goddess who embodies the feminine force of creation.

Not only had their attempt at in-vitro fertilisation succeeded, they had also successfully achieved the cryopreservation of an eight-cell embryo — storing it for 53 days, thawing in DMSO reagent and replacing it into the mother’s womb — a full five years before anyone else would do so.

He was also the first to use human menopausal gonadotrophins (hMG) to stimulate ovaries to produce extra eggs. As Anand Kumar later said, Subhash was “far ahead of his time in successfully using an ovarian stimulation protocol before anyone else in the world had thought of doing so.”

So Subhash’s method was different from — and, in the opinion of some, superior to — the one used by the English scientists RG Edwards and Patrick Steptoe for the birth of the world’s first test-tube baby in Oldham just 67 days ago (they did not freeze the embryo and their laparoscope technique of extracting eggs from ovaries was more difficult).

But unlike his counterparts in England, Subhash’s ground-breaking work did not receive acclaim and accolades from his countrymen. Instead, it was greeted with disbelief and disdain from the Indian scientific establishment.

Investigated by an official scientific committee that included no one qualified to evaluate his work, Subhash was vilified for making bogus claims, with the main thread in their argument being the doctor’s lack of documentation.

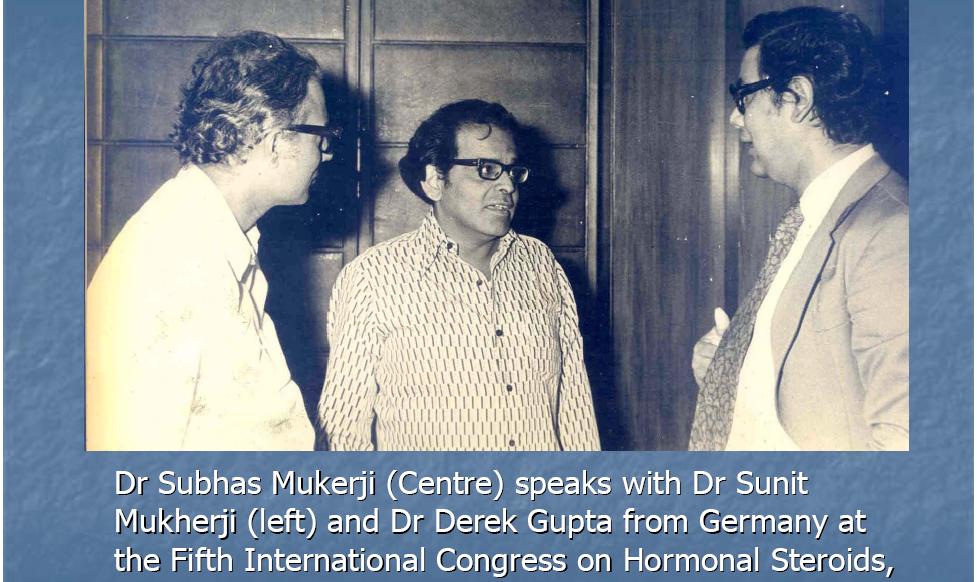

This reasoning is however spiritedly refuted by his teammate Sunit Mukherji who says that Subhash had published a paper in the Indian Journal of Cryogenics in 1978, presented his findings at the International Congress on Hormonal Steroids at Delhi the same year and even submitted a report on his work to the state government.

As for why Subhas did not physically produce Durga and her parents as evidence to consolidate his claim. the answer lies in the stigma associated with being childless in 1970s. Fearing social ostracism, the couple did not allow Mukerji to publicize the details of their daughter’s birth.

In an interview, Durga told the Livemint that her conservative parents weren’t prepared for the unsavoury media blitz that came with her birth and retreated from the public glare completely to maintain their privacy.

As such, Subhash continued to face opposition and ridicule. The vindictiveness and insensitivity of the institutionally backed gynaecologists’ lobby also prevented him from presenting his work to the international scientific community.

For instance, he was denied permission to travel to the Primate Research Centre of Japan’s Kyoto University in 1979, where he had been invited to discuss his work. In a final act of ignominy, he was transferred by the authorities to Kolkata’s Regional Institute of Ophthalmology in June 1981.

Humiliated and dispirited, Subhash committed suicide June 19, 1981, at his flat on Kolkata’s Southern Avenue. With this, India lost one of the most brilliant minds the country had ever seen. A decade later, his tragic story became the theme of Ek Doctor ki Maut, a National Award-winning film made by director Tapan Sinha.

However, it would take nearly a quarter of a century for everyone to stop doubting his story.

In October 2003, on the 25th birthday of India’s first test-tube baby, a function was organised by ICMR and Hope Fertility Clinic in Bengaluru in which the scientific community finally gave Subhash Mukherjee his due.

Durga, who was present, said, “I am not a trophy but proud to be the living example of the work of a genius. Justice has been done to my scientific dad.”

In 2007, the story of his life and work were included in the Dictionary of Medical Biography, a book published by Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, London, that lists the names of 1100 scientists from 100 countries around the world who have made path-breaking contributions to medical science.

A year later, during an event celebrating 30 years completion of IVF, Brazilian Medical Society also recognized and honoured Subhash for his incredible achievements. Interestingly, in 2010, RG Edwards was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for his work in developing in vitro fertilization (IVF) in humans.

A scientist par excellence, Subhash Mukherjee was the inventor of a modern miracle, one that would change the lives of millions of childless couples in the years to come. In fact, his method is currently the preferred technique of medically assisted reproduction worldwide. Its time we gave this forgotten pioneer the respect and recognition he deserves.

Also Read: Ignored For the Nobel Prize, This Unsung Scientist Is The Father Of Fibre Optics!

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167